Where is all the Coal Power Going?

Coal power has a long, rich, and very polluting history in the United States. Along with water, coal was the original power source behind the electrical revolution, and for over 100 years now it has been dirtying our skies, polluting our water, and providing us with the sweet sweet energy that we crave.

But lately, coal power hasn't been feeling too hot. In 2008, there were 1,514 generators using coal as their primary energy source, totaling some 340 GW of generating capacity. By 2024, there were only 479 generators with a total of 193 GW of capacity; that's a 40% drop in capacity over 15 years. So what's going on? Let's open up Hyaline and have a look around, and see what we can find.

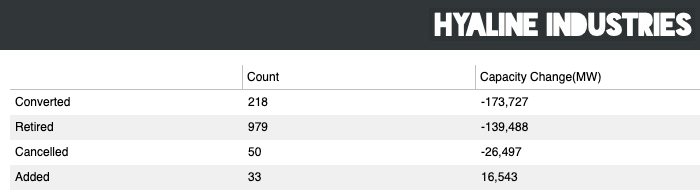

Between 2008 and the end of 2023, almost 1000 coal-fired generators shut down, and another 200 or so converted to using another fuel as their primary source. Adding pain to the misery, only 33 new generators were added in that time, and 50(!) generator projects were cancelled. There is one new generator in the works.

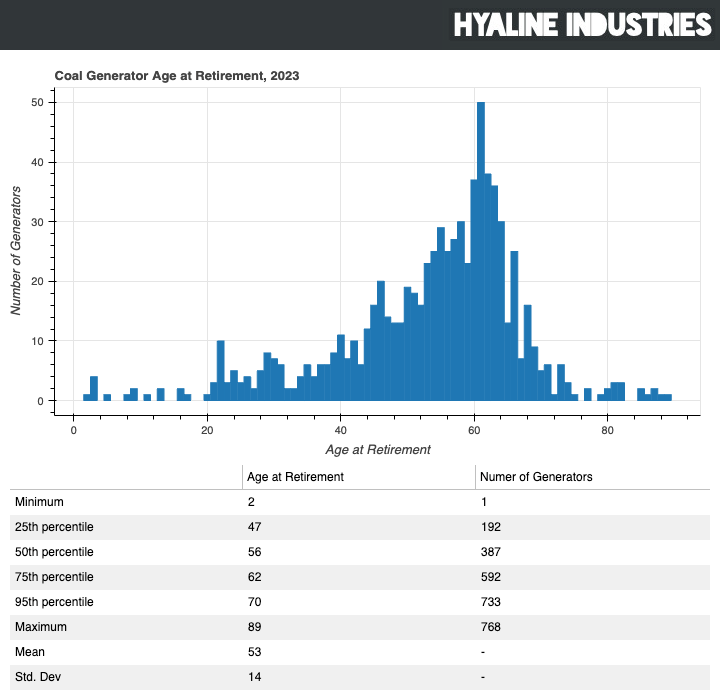

The big question that pops up at first: why are all these generators retiring? Let's dive in a little deeper and see. Start by taking a look at the age distribution of retired coal generators at the end of 2023:

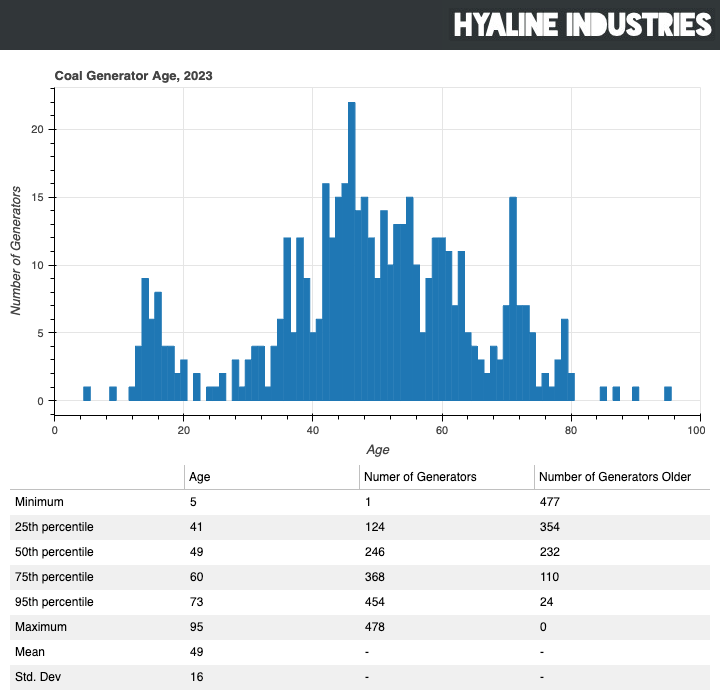

What you'll notice right away is that it is pretty rare for a generator to make it past 60: the average age of a generator at retirement is 53, and 95% of generators retired by age 70. Now let's look at just the ages of the generators which are still in operation:

There are a lot of old coal generators: within the next 10 years, we can expect to see around 200 generators reach their end of life and be retired, and within 20 we can expect around 350. By 2045, only about 100 will be left. And in fact, 120 generators have already been scheduled for retirement, 85 of which are slated to retire by 2030.

So basically, we have a bunch of coal generators, and most of them are old. Old machines wear out eventually and are shut down. So we're retiring a lot of coal generators right now. That's...not exciting. It does answer the basic question of why so many are retiring right now though.

This kind of thing clearly goes in waves. 75% of the currently operating coal generators were installed before 1985, and 50% before 1980, so clearly there was a big boom of new coal generators being installed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, probably because the previous generation of generators(installed in the 1910s and 1920s) were reaching their end of life. What's happening today with retirements is merely a repetition of the same exercise.

So instead of asking "why are generators retiring", the question should really be: "why aren't we building any new ones".

The total absence of new Coal Generation

Trying to suss out why there are essentially zero new coal units coming online is a tricky exercise, because it is largely guessing about counter-factuals. Still, we can look at a few of the arguments that are commonly suggested, and try to see if they hold water.

There are basically three arguments that are common:

- The modern grid, especially in power markets, incentivizes flexible power systems which can rapidly change their generation output in response to price pressures. Coal plants aren't particularly flexible, so they lose out or are forced to run at a loss, driving their profitability down.

- Environmental costs drive up the marginal cost of generating power from coal, causing profits to fall and expenses to become unrecoverable.

- The costs of building a new Coal unit is just too high compared to other available technologies.

Argument #1 can be discarded without too much thought, by just noticing the 200-odd generators that converted to a different fuel. Those generators are not suddenly more flexible because they converted to something else--the startup time is a function of the generator technology and the engineered design of the boilers, not the fuel used. And yet, the organizations that converted those generators did the conversions anyway! If grid flexibility were the only consideration, this kind of move would not make sense.

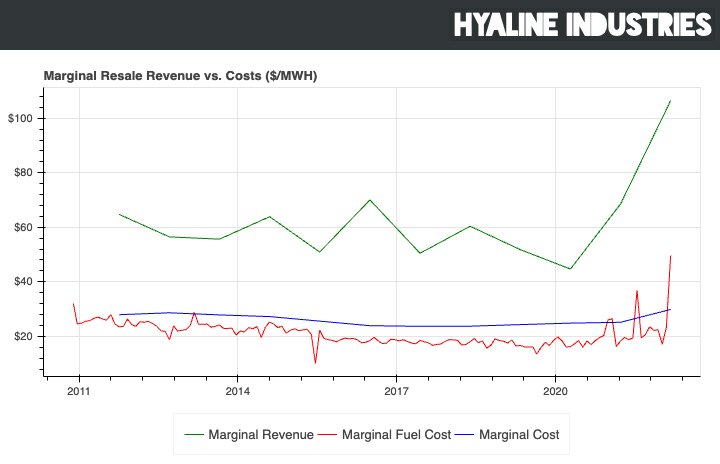

The second argument is built on the reality that coal is a very dirty, polluting fuel that imposes large operating costs. And this is true--compared to nearly every other available fuel, the costs of environmental mitigation of coal are exceptionally high. Unfortunately, that is a relative term. Here's a graph of the average marginal cost and revenue[1]:

Even a quick glance at the chart shows that fuel dominates the operating costs of coal plants, and the costs of pollution mitigation are significantly smaller. At the operating level, there is no reason to believe that coal is any less profitable than it was in 2008, so the sudden absence of new coal units probably shouldn't be attributed to the operating costs of coal.

Which takes us to capital expenses. Capital Expenditures are (at this moment) much harder to get a handle on than operating expenses: very few plants publicize them, and collecting information has (to-date) been a costly endeavor of tracking through regulatory filings and manually pulling that data out. There are at least a couple reasonably good studies that suggest that yes, in fact the capital costs to build a coal plant are really high compared to other energy sources[2]. Those costs are generally made much higher if you imagine that you're building it with a carbon-capture system, which is probably at least part of the reason the environmental cost argument is still deployed. This argument is the most compelling, partially because the evidence is there (although more scanty than we would wish), and partially because it's the last argument standing.

To make a long story short: Coal power is retiring because the fleet of coal generators is aging, and they aren't being replaced because there are cheaper options out there. It doesn't have much to do with the environment, or anything like that. It's just expensive. But it also means that, over the next 20 years, a bunch of organizations are going to have to shell out a lot of money to replace all these retired generators.

If you like this kind of analysis, be sure to tune in and follow along with Hyaline. Subscribe to this newsletter and see more cool ways we can understand our heavy industry!

Notes

- Taken from a sample of 300 or so coal-powered plants which report fuel receipts.

- If you want to nerd out, you can check out this USEA study from 2013, or the EIA's long-term modeling team's work in 2023, but the basic essentials are reproduced here

Like what you're reading? Sign up for our newsletter and get updates whenever we post new ones. And if you've got a question you'd like to see if we can answer, let us know at questions@hyaline.tech